Mill Creek Drowning

L. A. Nolan

"I've always been fascinated with the 'small town' mentality in the literary space. Authors such as Stephen King, Mark Twain, and Ruskin Bond write about it so eloquently that you can almost taste the dusty streets on your tongue. I wanted to explore that space, to blend literary and genre fiction and see what would happen to a mysterious antagonist when faced with the type of bias and judgment only a small town can provide."

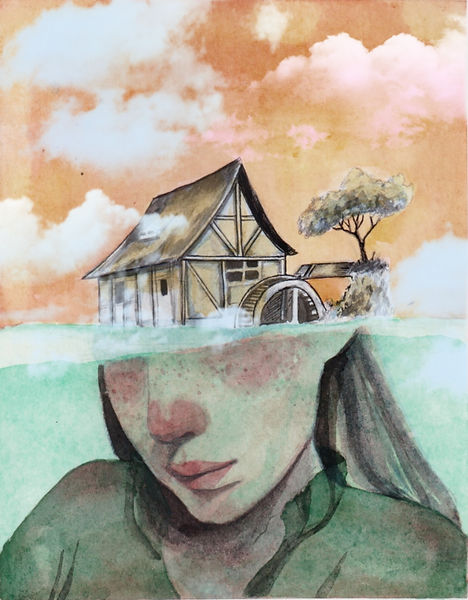

Artwork by - Tetsong Jamir.

Mill Creek Drowning

On the west bank of the Petoskey River, where the grey birch trees give over to the denser sugar maples and black oak, Mill Creek branches off from its big sister and froths its way north into the Walesnettesi Valley. It snakes through fields of purple coneflower and blushing pink mountain laurel until it reaches a dirt logging road. There, the creek doglegs north and flows alongside the road, passing Briar Hill and a tiny playground until it enters the small town that bears its name, to power the historic grain mill.

Folks figured the playground was most likely where little Abigail Finch went into the water that day. Behind the rusty swing set and stands of switchgrass. For years, residents requested a fence along the bank, and the municipal council had plans to allocate funds for construction, but unfortunately for Abigail’s mother—distracted with squeezing tomatoes at the farmer’s market and not noticing her daughter had detached from her skirt—it had not yet been built.

In the spring of 1939, Mill Creek was rife with apprehension. The Great Depression’s lingering effects—while seemingly overcome by the rest of the country—still burdened the residents, and the shadow of the Nazi war machine in Europe prompted fearful whispers of conscription among young men. They didn't need little Abigail's tragedy to underscore the atmosphere of the town's desperation. Particularly since her younger brother, Brody, had already caused an uproar. An incident involving the town’s resident outcast, Orton Edgworthy—a masked recluse living in a shack on Briar Hill—had set the tone.

So, things being the way they were that summer, some folks may not have blamed Abigail's misfortune on the lack of a fence at all had it not turned out the way it did. They more likely would have whispered to each other about retaliatory curses placed by evil Orton for her brother’s adolescent prank. Or perhaps they would have blamed Mrs Finch for being more focused on her shopping than her child. Or maybe they would have figured out a way to blame old Adolf himself. But, much to the residents’ horror, things did turn out the way they did, and that left the townspeople of Mill Creek feeling sickly and ashamed.

***

Brody Finch was a good kid. But he was also twelve, and eventually, through no fault of their own, all twelve-year-old boys seek out mischief. They are no more capable of restraining themselves from rascal-like behaviour than a rotten apple is of preventing its fall from a tree.

Not two weeks after school let out for summer break, Brody found himself crouched in a thicket of steeple bushes on the side of Briar Hill. His usual cohorts, Tommy Wilkinson and Ken Barnes, flanked him, along with Ken’s little brother, whom everyone just called Booger.

“Maybe this isn’t such a good idea,” Booger whispered.

His bravado had abandoned him now that they were within sight of Orton Edgworthy’s cabin. Most of the adults in Mill Creek believed him to be a Satanist, and Booger was only ten. He had not yet developed the intestinal fortitude required to execute a prank against such a man. Some of the older residents of Mill Creek remembered when Orton Edgworthy purchased the derelict dwelling on Briar Hill back in 1918, before the rumours and accusations, but for the boys, he had always been there and his demonic leanings were a fact.

“You,” Brody said sneering, “are a fraidy cat.”

“Am not!” Booger spat. “I just don’t want him to curse us, is all.”

Orton Edgworthy’s ability to cast the most atrocious spells was also a known fact and frequently discussed at Mill Creek’s general store around the pickle barrel.

“Pft. Go home then if you want," Brody said. “No one is forcing you to be here.”

He looked at Tommy and Ken for support, and in the moonlight, he could see that their eyes held shadows of apprehension and indecision as well.

“Any of you,” he added.

None of them, most notably Booger, showed any signs of abandoning the mission. Instead, they all gazed up at the cabin.

The abode suited a man with demonic tendencies. Rot had softened the cedar planks, the roof sagged, and night breezes flapped the torn front window screens. The porch was in such a dilapidated state that it threatened to collapse under the weight of a dog, let alone a human.

Brody, using his ability to throw a baseball from third to first base as a barometer, reasoned they weren’t close enough yet.

“Come on,” he said, and edged forward.

After a round of uneasy glances, the other three followed. Adolescent boys can be quite stealthy when they put their minds to it, and the four of them ascended the incline of Briar Hill like ghosts until Brody determined they were in range.

He dropped to his knees and unslung the burlap bag he was carrying from his shoulder. One by one, he withdrew a dozen rounds of their precious ammunition, each carefully wrapped in newspaper, and laid them on the ground. Over the previous week, the boys had shoplifted the eggs one at a time from the farmers’ market. It had been a daunting task that they somehow executed without being caught.

Brody unwrapped the eggs and shared them out, three apiece.

“Make every shot count,” he said. “Most points for hitting the door or a window.”

“Oh, man,” Ken whispered. “We really gonna do this?”

Instead of answering, Brody popped up and fired the first round. The eggshell glinted in the moonlight as it sailed straight and true, then splattered on the door jamb beside the handle.

“Yes!” Brody hissed.

Realising that they had drawn first blood and were well past the point of no return, the boys let loose the rest of the opening salvo. Ken’s egg scored a window hit, Tommy’s exploded on the porch, and Booger’s best effort resulted in a pitiful misfire and fell well short of the cabin.

The porch light burst to life immediately. It seemed as if old, evil Orton had been standing with his hand on the switch. The cabin door opened as the boys released the second volley. One hit the porch rail, another cracked against the wall, and Booger’s egg reached the steps. But Brody’s shot, well, that hit the mark.

Orton had walked out onto the porch and, silhouetted in the yellow lamplight, presented himself as a fine target. Brody never said if he had thrown his egg at Orton intentionally, but it connected with him square in the chest with all the ferocity of a run-saving hurl from a shortstop to a back catcher.

Orton raised his fist and shook it at the dark figures in his yard. He yowled and cursed, yet while his expulsion was in English, his voice was thick and unintelligible, holding no articulation. His words echoed off the hills as if they were here, and in some far-flung realm of nightmares. He stepped off the porch and onto the stairs, his boot landing in the gooey reminiscence of Booger’s second toss.

With adhesion lost, Orton’s foot shot forward into space, and he toppled. Illuminated by the front door light, the boys saw him reach desperately for the railing. His stubbed fingers brushed against it, then came up empty.

He landed hard, planks splintering under him with a sharp crack while his head slammed against the porch with a thump. The boys scampered away into the blackness like frightened mice, leaving the remaining four eggs abandoned on the ground.

***

People knew little about Orton except that he immigrated from England, and after settling on Briar Hill, he quickly established a routine that remained unchanged for twenty years.

Every eight weeks, Orton would descend the rutted path from his cabin, pass the playground, and march through town. First, he would pay a visit to the post office, then cross the street and enter the bank. He would ignore any queue, should there be one, and go straight to the teller.

After making a deposit, he would stop by the general store, the butcher, and the farmers’ market. He presented the proprietors with a comprehensive list of items, who would then despatch deliveries fortnightly to his home. Other than a biannual book order from the local school-cum-library, that was the extent of Orton Edgworthy’s interactions with the people of Mill Creek.

His age was unclear, as despite his young, athletic build, Orton’s hair was virgin white and his face offered no clue because of the painted copper mask that concealed it—the mask that wore an unnerving and barren expression.

The bank tellers and store clerks relayed stories of his stuttered, dull speech, his scarred neck and hands, which fuelled rampant rumours of deformity or a serious affliction.

The whispers of disfigurement quickly changed to suspicions of devilry once the inhuman wailing began. Horrid screeches of unmitigated terror would often emanate from his cabin in the dead of night. On the first few occasions, the sheriff dutifully investigated. After allowing a cursory look around his home, and a harsh reprimand, Orton bade the sheriff to leave him in peace, as he was performing no wrong. The morbid screams of dread and dismay lessened over the years, but still occasionally rang out to unsettle the folk that lived close enough to Briar Hill to hear them.

***

When Orton appeared trudging down Main Street early in the morning after the egg assault, a week before his normally scheduled appearance, the news travelled along the gossip wire faster than a greased pig. It got folks curious in all kinds of ways, especially when he walked right past the post office and continued on to see the sheriff. The forty minutes Orton spent inside the station house was ample time for the general store’s pickle barrel scandal and slander committee to convene and formulate their hypotheses.

For Mill Creek, Barn’s General Store was beyond just a place to shop; it was a community gathering spot, a safe space where neighbours could catch up on local news and share stories. Vintage advertisements and antique signs adorned the walls, while faded photographs told the story of Mill Creek’s history. The aged wooden shelves and counters, darkened by decades of use, held rows of glass jars brimming with colourful candies and spices. But most importantly, the heart of it all was the large pickle barrel by the entrance. Surrounded by three chairs and an old milking stool, it served as the committee’s unofficial meeting point.

“I’m betting he’s killed someone in one of his rituals and come to confess!” Mr Barns said.

“Or worse,” Mrs Finch piped in. “To justify it! Most likely saying the poor soul was a trespasser or breaking into his home. A plea of self-defence!”

Little Abigail was sitting on the floor at her feet, playing with a Raggedy Ann doll. She looked up at her mother.

“What’s a treppapper?” she asked.

“Not now, darling,” Mrs Finch said, and she fished a spearmint candy out of her skirt pocket. Abigail popped it in her mouth and went back to her doll.

“Or to report finding the body. You know, as a cover-up!” Mr Barns said.

“He may have gone to the sheriff to complain about one of us. To find out where we live or such, so he can place a curse.” Mrs Wilkinson said with a shiver.

In the spring of 1921, when Orton began ordering books, his choice of literature did little to stem the consensus that he was a devil worshipper. According to the spinster, Ms McClellan, a librarian and teacher, his preferred readings were texts of the occult and macabre. The sheriff at the time—who didn’t partake in the general store gossip—warned that judging a man based on his chosen reading material was folly. His voice went unheeded, and after a severe crop failure that summer and an unexplained rash of livestock disease, the die was cast, Orton was blamed, and he was unceremoniously declared to be in league with Satan.

There were rational folk as well. Ones who believed Orton was simply a man afflicted with some type of ailment who wanted nothing more than to be left in solitude. But fear of the unknown is a powerful thing in small towns that share a group disdain for outsiders. Through the years, the townspeople blamed Orton for many of their misfortunes until an unspoken agreement formed between the two—Orton ignored Mill Creek, and Mill Creek did its utmost to ignore him.

“Has anyone crossed him recently?” Mrs Finch asked.

There was a chorus of no's, and the theories continued to formulate, each more gruesome and fantastical than the one before it, until Sheriff Donaldson entered through the squeaky screen door, and their chatter fell silent.

“How lucky you’re all here,” he said, although his expression clearly showed no surprise. “Mrs Finch, Wilkinson, Mr Barns, could you round up your boys and bring them over to my office for a little chat? In an hour, let’s say?”

“Oh God! Why?” Mrs Wilkinson blurted.

The sheriff held up his hand and shook his head.

“In an hour, please,” he repeated, then spun on his heel and left the general store to its gossip.

***

Booger was the first to crack. The boys were positioned in a line before the sheriff’s desk, red-faced and sullen, while their parents stood behind them with folded arms. Sheriff Donaldson hadn’t even asked any questions yet; he had just retold the tale Orton had relayed to him earlier, and tears sprang from Booger’s eyes. They rolled in torrents down his cheeks as he blubbered his excuses.

“I didn’t want to!” he said. “I told them it was a bad idea.”

Ken kicked his younger brother’s foot hard and hissed at him to shush, but Booger laid bare his soul.

“They made me steal eggs from the market. I didn’t wanna!”

“Oh geez. Shut up, Booger!” Brody said, and his mother gave him a cuff across the back of his head.

“You hush, you little cretin,” she scolded. “When your father hears about this…”

Abigail, fixed to her mother’s skirt as usual, was unsure what was happening, but giggled at the fact that her brother had just received a smack. Brody glared at her.

“Well, Sheriff,” Mr Barns said. “Obviously, there is no doubt about guilt. The question is, what are you going to do with them?”

Sheriff Donaldson looked out his office window and watched the waterwheel on the old mill make a half dozen rotations before speaking.

“If I had my way, they would hustle their behinds up there to clean his yard for him,” he said.

“God, please, no! I don’t want my boy anywhere near that place!” Mrs Wilkinson said.

“Well, Tommy doesn’t seem to mind getting close,” the sheriff said. “Close enough to pelt the man’s cabin with eggs.”

Mrs Wilkinson fell silent and looked at the floor while the sheriff shifted his address to the boys.

“But Mr Edgworthy just wants to see y’all reprimanded, nothing more. I’ll have to speak to Joanne at the market about the eggs, but you can bet you’ll at least have to pay for those. Out of your allowance or by doing chores, I imagine. The discipline I’ll leave to your parents.”

Brody, Tommy, and Ken all moaned, and Booger just continued to cry.

On the front steps of the sheriff’s office, the three parents, after shushing their boys back home, shared an uneasy silence. No one wanted to say what they genuinely feared, nor did they know how to give voice to it. No longer able to bear the tension of the situation, Mrs Finch spoke up.

“Just a reprimand? I pray that’s all he wants.”

“Repimant,” Abigail whispered.

***

After the incident, amid an eerily silent night, the screams from Briar Hill began again, shrieks filled with such terror and desperation that they reeked of unimaginable horrors. They came in bursts, each one more frantic and gut-wrenching than the last, as if the poor soul was being tormented by some paralysing nightmare. The pitch of the wails rose and fell in an unearthly fashion, making it impossible to tell whether they belonged to Orton or something else entirely. Over the next several weeks, the calls abated, but that did little to comfort the parents of the boys. They spent the waning dog days of summer on pins and needles.

***

On the morning of the last Friday in August, dawn broke heavy. The atmosphere was close and damp due to a thunderstorm the evening before. As the sun was dissipating the mid-morning mist, the residents of Mill Creek joined the day and became lost in their routines.

The open-air farmers’ market across the mill was welcoming its first customers, one of whom, Mrs Finch, was so intent on selecting the plumpest and firmest tomatoes that she was deaf to little Abigail’s murmur.

“See paw,” she whispered, spying the playground. The tot let go of her mother’s skirt and silently wandered away.

Lost in his thoughts, Sheriff Donaldson didn’t notice Abigail crossing the road as he strolled down Main Street. Most mornings, as was his routine, the sheriff bought the daily newspaper and grabbed a cup of coffee from the corner diner before embarking on his march around town. Not only did he believe that public visibility was crucial for effective policing, but he also enjoyed the walk.

The sheriff passed the mill and noted that the paddle wheel was spinning a touch faster than usual, powered by the swelling of the creek from the previous night’s rains. His gaze fell to the feeder canal, and he saw the water frothing and gurgling between the wired stones of the retaining wall.

Glancing up, he noticed Orton Edgworthy skulking, in that peculiar gait of his, along the gravel path leading from the playground towards town. He was approaching the culvert where Mill Creek spilt off into the adjacent canal. The sheriff raised his hand in greeting. Orton flinched in reciprocation, then suddenly snapped his head back over his shoulder. The sun glinted off his copper mask as Orton spun, and then he started for the creek bank in a panicked lope. The sheriff tensed and strained to see what had agitated him.

“Orton?” he called and jogged forward.

“The girl! Girl…”

Orton delivered the reply in his thick, muffled voice, and the sheriff couldn’t quite understand him; then, in horror, he did.

The sheriff’s breath hitched as he spotted Abigail’s tiny figure, limbs thrashing against the churning creek. Panic surged in his chest. He sprinted, the ground blurring beneath him. Time seemed to stretch and compress all at once, every heartbeat a pound of a drum urging him onwards.

Orton splashed into the water, fighting against the pull of the current as he clawed towards the girl. He managed to get hold of Abigail, and now they were both tumbling in the direction of the feeder canal at a furious pace. The sheriff’s pulse quickened as he realised he might not reach them before it was too late. He slowed for a split second, torn between changing direction and running back to disengage the switchgear or continuing to the canal. He glanced back at the mill. The paddle wheel, which was normally a cheery display of nostalgia for all to gaze upon and enjoy, had become a heinous instrument of death. It spun hungrily. The droplets cascading from the paddles glistened like saliva dripping from teeth, and the indistinct murmur of the timbers took on the intonation of a rumbling stomach.

Sheriff Donaldson had to choose— the switch gear or helping Orton. Both seemed an impossible task. Orton was kicking his legs and desperately pulling with his free arm to reach the bank. It was going to be close, and the sheriff knew that if they entered the canal, there would be no stopping the tragic outcome. He forgot the mill and charged ahead, focused only on saving the child.

“Someone, kill the switch gear!”

For one chilling moment, he felt he would be too late, but a surge of adrenaline saw him reach the creek moments before the pair passed into the feeder canal. As he plunged into the waist-deep water, his gut twisted, watching Abigail flail. Every town meeting where the fence had been postponed flashed through his mind. The current began tugging at his legs, trying to draw him deeper, so he jammed his back against the abutment wall and thrust out his hand.

Now, Orton was really struggling. Little Abigail was in full hysteria, kicking and slapping, almost causing him to lose his grip on her. Her screams came intermittently as she bobbed up and down out of the creek. Her tiny fingers, slick with moisture, were grasping and clawing, seeking any purchase to keep her head above the froth. She hooked Orton’s mask and ripped it free. The painted copper facade flew through the air, then hit the water and sank.

What lay beneath was neither a hero’s face nor the imagined demon of the town’s gossip but something entirely different, something twisted and broken. Scarred skin pulled tight over hollowed eyes. A nose that was a blunted ridge, and lips, skewed and uneven, hinted at the mouth they once were.

The sheriff felt a chill run through him and a wave of nausea rise, but he fought it down. He swallowed hard and then realised with shock what Orton was intending to do.

Orton had given up paddling for fear of losing his grip on Abigail. Instead, he had grasped her with both hands around the waist. But his trajectory was wrong; he was too far from the bank. The sheriff would never be able to get a hold of both of them. Orton was going to hand her off. This man, this figure the town had feared, was gambling with his life for a child who didn’t know him.

“Take her!” Orton’s voice was rough, choked with desperation.

“No! Swim!” the sheriff shouted.

It was too late. Orton had made his choice. The sheriff locked eyes with him. They were pleading as he fought the current. He knew he wouldn’t make it, and the sheriff saw a moment of resolution cross his misshapen face. With one final, desperate push, Orton heaved Abigail towards the bank. The sheriff lunged forward, his hand closing around her wrist just as the water threatened to pull her under. He barely had time to register the sacrifice Orton had made before he was swept away. The sheriff yanked hard, drawing a squeal from the girl, drew her close and wrapped her in his arms. The sheriff scrambled up the sodden incline and handed the wailing child to her frantic mother, standing among the crowd of terrified spectators.

“What has that beast done to my baby girl?” Mrs Finch screamed.

The sheriff turned and spotted Orton halfway down the canal and tumble helplessly towards the water wheel.

“He’s saved her,” he whispered.

As Mrs Finch clutched Abigail to her chest, tears spilling down her cheeks, the rest of the onlookers watched in silence as Orton approached the bubbling foam created by paddles slapping the water. There came a collective gasp as the current pulled his gruesome face beneath the surface. The wheel shuddered and stopped. Orton’s body had lodged itself between the bottom of the canal and the paddleboards. The moment froze as the gathered townsfolk cried out in dismay; then the mill issued a deep, sorrowful groan and after a slight tremble, the wheel began to rotate again.

***

Sheriff Ralph Donaldson was not prone to emotional displays. He was a thoughtful and compassionate man, yet stoic, and rarely could one tell what he may be feeling. Such was not the case as he sat at the rickety wooden desk in Orton Edgworthy's cabin.

After retrieving his body from the canal—his coveralls had snagged on the retaining wall wire on the wheel’s discharge side—the sheriff took Orton’s remains to the morgue and then went to his cabin to find information about his next of kin.

As he sifted through the documents, the mystery of Orton’s life unravelled. A solid lump formed in his throat, and his eyes misted.

The sheriff learnt from the town doctor that Orton’s disfigurements were the ghastly result of exposure to mustard gas. Now, reading his discharge papers, the sheriff discovered Orton had been a highly decorated soldier who served valiantly in the trenches of France during WWI. He shook his head as he stared at the small wooden box containing a Silver War Badge, a Distinguished Service Order, and a Military Cross.

Next, he read the letters of correspondence from his loving sister in London. They wove a tale of disrepair about how Orton, after being discharged from the army, had suffered from extreme episodes of shell shock and how he had left the care of his sister and her family because his bouts of night terrors were traumatising her young children. Orton had taken his dismissal discharge payment and used it to purchase a cabin in America to shield his loved ones from his horrible appearance and uncontrollable deviations into madness. For the past twenty years, he had lived in solitude, surviving only on the meagre amounts of coin his sister could spare for him.

The sheriff felt dirty reading the letters, as if he were tarnishing Orton's memory. He, as did most of the Mill Creek townsfolk, held vulgar opinions about him. How incorrect he had been. How woefully incorrect they had all been. A single tear rolled from his eye and fell, landing on the desk. A dark stain formed as the dry wood soaked up the salty brine.

**END**

L.A. Nolan is a fiction author whose work includes thirteen short stories in various literary and genre anthologies. He was recently shortlisted for the Westland IF novella competition, his short story The Peddler & the Crow, won the Indian Writing Projects grand prize season 5 and As the Banyan Tree Wept was shortlisted in the Indian Film Project season 7. His novels to date: Memoirs of a Motorcycle Madman, a humorous travelogue. Blood & Brown Sugar, a crime thriller, A Crate of Rags & Bones, a horror short story collection, and Blood & Bombay Black, a crime thriller.

© The Ink & Quill Collective 2025. All rights reserved.

FOLLOW US ON

Or drop us an email at -

theinkandquillcollective@gmail.com

inkquillcollective@arijitnandi.com