PINNI

Harshita Nanda

"I wrote this piece because I had just finished making panjeeri for my sons. I had used the recipe of a Pakistani vlogger. I was struck by the fact that even though the lady was from a supposedly different country, her mannerisms, language, and food were familiar to me. We both were Punjabis, even though a line divided us. This commonality of food is what was the seed of the story. "

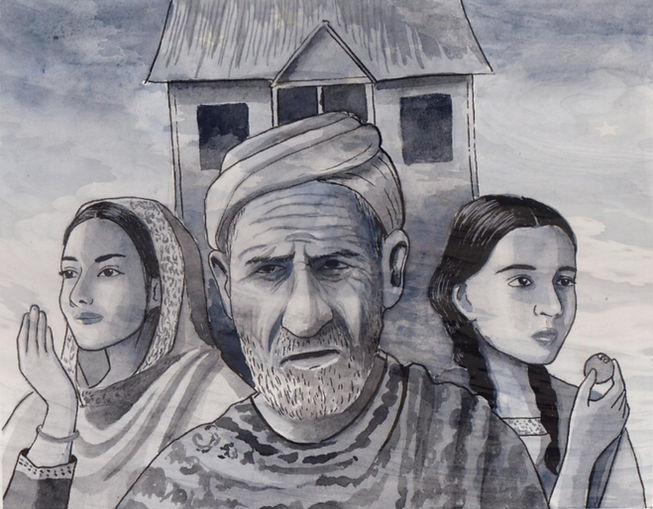

Artwork by - Tetsong Jamir.

PINNI

Septuagenarian Pushpendra Sharma was a man with firm principles and beliefs. For more than thirty years, Pushpendra had worked as an accountant in a firm in London before retiring to a small village in Berkshire, where he was the only brown resident amongst the population of ten thousand. The solitude of village life suited Pushpendra; he had, after all, been alone most of his life. Set in his way, his routine was the one constant in his life.

That day was no different. He awoke before daybreak, and after ablutions, sat in his prayer room to do his daily meditation and chanting. But even though the morning started as normal, it wouldn’t continue to be so.

As the clock ticked seven, the doorbell rang. He tried to ignore it, but a brisk knocking followed the ringing. Irritated at the interruption, Pushpendra got up from his prayer stool. Clutching the doshala around his shoulders to ward off the early morning chill, he opened the door to glare at the young woman outside.

Wearing a salwar kameez, her head covered with a gauzy dupatta, she raised her cupped palm to her forehead. “Adaab, uncle. My name is Amreen. My son and I moved into the house across the lane yesterday. I have yet to unpack. Can you please lend me a small bowl of sugar? It is too early for the grocery store to open, and it is his first day of school.”

Pushpendra stared at her for a few minutes before giving a short nod. Ignoring the bowl she held out, he gruffly said, “Wait here.” Leaving her at the door, he shuffled to the kitchen.

Clutching the bowl, Amreen peeked in. Framed paintings of gods covered the walls of the corridor, which led into a room that looked like a prayer room. Tendrils of aromatic incense curled out from it. Giving Pusphendra a bright smile when he returned with a bowl in his hand, she pointed to the toran that adorned the doorway and said, “we are new in this village, in fact, the country. The toran told me this house belonged to a person from the sub-continent. I was so relieved that someone from our part of the world lives in the same lane. I am still not comfortable with the goras. That’s why I didn’t hesitate to ask you for sugar.”

Ignoring Amreen’s chatter, Pushpendra replied, “don’t bring back the bowl.”

Amreen noticed he was careful not to touch her hand while handing her the bowl.

Bemused at his quirk, she nodded, adding, “thank you, Uncle. I have moved here from Lahore. Are you from India?”

Instead of answering her question. Pushpendra slammed the door shut.

Amreen frowned. How rude! She thought, but hearing Shoaib shouting from across the lane, she hurried back home.

Inside, Pushpendra washed his hands with ganga jal and resumed chanting. However, he found his mind wandering to the young woman. Her adaab and the gauzy dupatta niggled at a memory he had locked away for more than sixty years. Of a tinkling laugh and a soft hug that made him feel safe. Lahore…the word repeated in his mind. With a frustrated growl, he got up, chalking another point against his new neighbour.

***

“Ammi!”

“Have some patience, Shoaib! I will warm the milk in two minutes!” Amreen exclaimed, walking back into her kitchen.

“I can’t be late on the first day of school. As it is, I will be the new kid in class. If we were in Lahore, Badi Ammi would have made my tiffin and had the milk ready even before I got up!” he muttered, pushing books in his school bag.

“Well, we are not in Lahore anymore. We need to grow up and become responsible for ourselves.” Off-kilter from her run-in with Pushpendra, Amreen snapped back.

Immediately, she wished she had not raised her voice. Shoiab’s lower lip had started to tremble. Sighing, she reached out to hug him.

“I don’t like it here. It is too cold. I want to go back to Lahore,” Shoaib sniffled against her shoulder.

Amreen drew back and gazed into his dark eyes. Eyes that he had inherited from his father. Ignoring the stab of longing to see her lover's eyes on her son, Amreen said, “I know you miss Lahore, your grandparents and your cousins. I also know you are anxious since you don’t have any friends here. But for my sake, can you look at this as an adventure?”

Shoaib looked at the sheen in his mother’s eyes and nodded.

“Now, how about I drop you off at school on my way to work? That way you won’t get late?”

Shoaib grinned. Grabbing his bag, he shouted, “race you to the car!”

***

Shoaib kicked a stone as he walked home from the bus stop at the end of the lane. The first day had not been as bad as Shoaib had imagined. Yes, he was the only brown child in the class, but the other kids had mostly ignored him. They were more interested in the ball Peter had received as a gift from his father. Shoaib didn’t know if the longing he had felt on seeing the happiness on Peter’s face was for the football or the fact that Peter had a father. Amreen had told Shoaib that his father was a good man. This was why Allah Miya had called him to Jannat. But he wished Allah Miya had thought a little about Shoaib, too.

Shoaib sighed. He tried to be supportive of Ammi when she worked so hard to give Shoaib the life his father had dreamed of but some days, he just felt so lonely.

He had reached the driveway of their house when he spotted Pushpendra trimming the hedges. The slight stoop of Pushpendra’s shoulders and his bushy moustache reminded Shoaib of his grandfather. He glanced at the empty house behind him, it was still a few hours for Amreen to be home from work, before looking towards Pushpendra. Coming to a decision, he moved closer towards Pushpendra’s house and called out, “hello Uncle, I am Shoaib. Do you need any help?”

Pushpendra ignored him, just as he had ignored Amreen in the morning.

Shoaib stood watching him for a few more minutes before shrugging his shoulders. One thing he had learnt in his eight years was that older people were often moody. He ran up to his house, but as he slammed his door shut, he saw Pushpendra staring at him.

***

A couple of days after she borrowed sugar, Amreen tried to return the bowl to Pushpendra, filling it to the brim with sevaiyan.

“I told you the bowl is yours, no need to return it,” Pushpendra said from the door. He once again didn’t invite her inside.

“But uncle...”

Pushpendra held up his hand to stop her words. “I am a Hindu from India. You are a Muslim from Pakistan. Our countries and religions do not get along. I do not want to have anything to do with you. Neither your courtesy nor your sweets nor your friendship. Please do not come here again.”

Amreen flinched as Pushpendra slammed the door shut. A few minutes later, the shock of Pushpendra's blunt words gave way to anger. Amreen felt the blood in her veins throb. She looked at the bowl of sevaiyan in her hands, wanting to hurl it against the door. She stomped back to her house, vowing to ignore Pushpendra if she ever saw him on the street.

Pushpendra and Amreen, though tied by the commonality of the colour of their skin, became neighbours who ignored each other.

On the other hand, unaware of Pushpendra and Amreen’s interactions, every afternoon, Shoaib would wave and call out to Pushpendra, who would be pottering in his garden. And every afternoon, Pushpendra would ignore him. What started as a lonely boy’s attempt to make relations turned into a battle of stubbornness with Pushpendra.

Yet, all of Pushpendra’s efforts to ignore his new neighbours failed.

Every evening, when Amreen would cook dinner, Pushpendra’s nose would twitch. His bushy eyebrows would come together in a frown as the tempting aroma of onion and garlic browning in masalas would waft over from across the street.

He would look at his simple dinner, but instead of the bone china plate, he would see a dented steel plate with a portion of food that he knew would not satisfy the hunger gnawing in his stomach. He would recall a voice muttering, “Anwar is living like a king in Lalaji's haveli, while we struggle to eat khichadi even once a day.”

He started evening chanting sessions to divert his mind from his memories and the activities of Amreen’s kitchen.

***

One day, when Pushpendra sat down to dinner, he noticed there were no aromas from Amreen’s kitchen. Usually, this happened on the weekend, when he would scoff at the delivery rider who would appear carrying the pizza box. But today was a weekday.

But what is it to you, if Amreen cooked dinner or not? He scolded himself, picking up his spoon.

Suddenly the doorbell rang, followed by insistent knocking.

“Uncle! Uncle!” shouted a voice from the other side.

These people will never let me live in peace, he thought, shuffling to the main door. But his irritation changed into alarm when Shoaib collapsed in his arms as soon as he opened the door.

“Ammi! Ammi!” Shoaib wheezed, pointing towards his house.

Grabbing Shoaib’s hand, Pushpendra crossed the street to find Amreen senseless on the kitchen floor.

Looking at her still form, Pushpendra’s heart hammered. He remembered another woman lying on the floor like this. The same feeling of helplessness washed over him. Frozen, he stared at her until Shoaib tugged hard on his hand.

“Do something!” Shoaib wailed.

Snapping out of his stupor, Pushpendra rushed to Amreen’s side. Chafing her hands, he asked, “have you called the ambulance?”

Shoaib stared at him, bewildered. Pushpendra said, “get me the phone! Fast!”

An hour later, Pushpendra sat with his eyes closed on a grimy plastic chair in the emergency room. He hated hospitals and the underlying sense of despair that filled the atmosphere. A soft sob made Pushpendra look down at Shoaib, who sat in the chair next to him. His hands in his lap, Shoaib’s shoulder imperceptibly leaned against Pushpendra’s.

He hadn’t wanted to come to the hospital or get involved. But he knew Amreen only had Shoaib. He hadn't seen anyone else visit them since they had moved in. Pushpendra felt an unfamiliar emotion rising in his heart. He had once known a boy who had been as lost and bewildered as Shoaib was. “She will be ok,” he said, feeling the need to do something, say something.

Shoaib looked at him, his lashes damp. “Promise?” he asked, his lips quivering.

Pushpendra swallowed and nodded. His hand lifted as if to hug Shoaib when the doctor called out to them. Amreen was conscious.

***

“Ammi!” shrieked Shoaib, running to hug Amreen. Mother and son laughed and cried, hugging each other.

Pushpendra stood in the doorway, not yet ready to enter the room, his eyes taking in the IV in Amreen’s arms and the surrounding monitors.

“The doctor said you fainted because of low blood pressure. Plus, you are anaemic. What kind of mother are you that you can’t take of yourself for your son?” he growled.

Amreen looked at him over Shoaib’s dark head. Her eyes glistened with unshed tears. She ignored his rebuke.

“We are obliged. Thank you for helping us,” she replied before turning back to kiss Shoaib and assure him she was fine. Her actions told Pushpendra he was no longer needed. He looked at the mother and son for a few more minutes before heading home.

The next morning, Pushpendra got up at his usual time. But his feet, instead of entering his prayer room, walked into the kitchen. He inspected the contents of his refrigerator before turning on the cooking range.

At eight, Amreen was surprised to see Pushpendra in her hospital room with an old-fashioned brass tiffin box in his hand.

“You can eat vegetable porridge for breakfast,” he said, handing her the tiffin. “I spoke to the doctor on the way in, and he said by twelve you will be discharged. I will take you home. Shoaib has gone to school?”

Baffled by the sudden change in Pushpendra’s manner, Amreen could only nod.

“Eat,” said Pushpendra, sitting on the only chair in the room. Flapping the newspaper open, he proceeded to ignore Amreen.

Amreen pulled the tiffin towards her, peeking a look at the man, who, until yesterday, had not even wanted to look at her. In his tweed coat and corduroy pants, his appearance reminded her of her father. But Pushpendra had always been rude and gruff to her.

“I could have eaten something from the cafeteria,” she protested.

“It might not have been halal,” he replied, turning a page. “This is vegetarian.”

Surprised and a little touched that he knew about her dietary restrictions, Amreen picked up the spoon and silently finished the porridge after that.

Later that afternoon, Pushpendra drove Amreen home. His manner remained as gruff as before and he didn’t dawdle, leaving her on the doorstep, but Amreen could feel a slight softening in his shoulders.

A week later, Amreen walked up to Pushpendra’s house. In her hand was the brass tiffin box Pushpendra had taken to the hospital.

“Uncle, I know you may not eat it, but hearing of my ill health, my mother sent some pinnis. I don’t like being beholden to strangers for favours. So, consider this as a payment for your help,” she said, placing the tiffin box on the floor near the door. Before Pushpendra could reply or react, Amreen walked away.

Befuddled, Pushpendra picked the box and placed it on the dining table. The clock ticked away the hours as Pushpendra followed his daily routine, but he couldn't help himself from glancing at the tiffin every few minutes.

The aroma of onions browning from the house across the street snapped him out of his stupor. In a daze, he lowered himself to a dining table chair. Dragging the tiffin towards him, he slowly pulled it open. A dozen pinnis were arranged in neat concentric circles.

Hesitantly, his hand reached out and picked one. He took a small nibble. The flavour of ghee-roasted flour, sugar and nuts burst on his tongue. His bites became larger, and soon his hands were empty. The only thing that remained was the stickiness of sugar and ghee lingering on his lips. And fragmented memories that he had long suppressed.

***

“Wipe your face!” she laughed, wiping his mouth with her dupatta.

“Why should I do it when you are there to do it for me?” Pushpendra grinned, his eyes shining with mischief.

“See how your face has dirtied my chunni,” she replied, showing the stain of ghee on her dupatta.

“That’s the price you pay for loving me,” the five-year-old replied, hugging her.

Naseem laughed at his words, ruffling his hair. “And pray what will happen when you marry and your voti kicks me out of the house?”

Pushpendra’s arms tightened around her. “I will kick her out instead. We will always stay together, aapa!”

Naseem laughed louder, her brown eyes dancing. Dropping a kiss on his forehead, she said, “now run along and let me finish the chores. Else Lalaji will scold me.”

“Can I take another pinni?” he pleaded.

Naseem chuckled, handing him another one from the big tin canister where she stored them. Clutching the treat in his hand, Pushpendra ran out to play.

That night, as Naseem sang a lullaby to put him to sleep, Pushpendra thought about how lovely his life was. His father was the biggest land owner in the village on the outskirts of Lahore. Kind and fair, everyone used to respect Lalaji, as he was called. Pushpendra, on the other hand, was a mischievous brat. The only one he would listen to was Naseem, who was part ayah, part maid, part cook in Lalaji’s household. When Pushpendra’s mother lost her life a year ago to a winter chill, it was Naseem who became his surrogate mother.

Naseem, in her pastel shade salwar-kameez, her head always covered with a gauzy dupatta, was much sought after by the village’s young men. But Naseem inexplicably felt responsible for Pushpendra and refused to marry.

Their idyllic days, however, didn’t last long.

Hot winds were blowing across the subcontinent. A line was being drawn through the country to create two countries from one. An invisible line, based on religion, divided their village as well. These lines appeared on the forehead of Lalaji too. Leaving Pushpendra in the care of Naseem, Lalaji decided to go to Lahore to find out more.

Neither did the monsoon clouds arrive, nor did Lalaji return. Naseem’s eyes too slowly lost their sparkle. The people of Pushpendra's community ignored her. She didn't belong to their religion. Her own community ostracised her, calling her a collaborator for taking care of a child from the other community. She stopped stepping out, keeping Pushpendra close to her.

What Pushpendra remembered of that fateful night was how oppressive the air was, making each breath laborious. It seemed that the entire universe was waiting, watching how the night would unfold.

The mob had burnt down a Hindu house the night before. Naseem had tried to distract Pushpendra with stories, but he had heard the screams. It was only a matter of time before the mob hit Lalaji’s house. Naseem had spent the day burying the valuables Lalaji had left behind. As the evening came, she refused to light the lamps. Instead, she lit a single candle in the courtyard. Her anxiety increased with the lengthening shadows.

Pushpendra had fallen into a fitful sleep holding Naseem’s dupatta as she whispered duas over him when a loud knock on the door startled him awake. As the knock was repeated, the street dogs howled in unison.

Naseem looked at the door, her eyes wide with fear, while Pushpendra clutched her arm.

“Naseem bibi, open the door. It is me, Bhola!” came a loud whisper from the other side.

Naseem and Pushpendra looked at each other. In happier times, Bhola had been one of Lalaji’s trusted farm workers. But could they trust him now that the times had changed?

Gesturing to Pushpendra not to make a noise, Naseem clutched a kitchen knife behind her back before opening the door. Pushing her inside, Bhola bolted the door shut. Looking at Pushpendra, half-hiding behind the charpoy, he said, “the mob is making plans to attack the house tonight. You need to run.”

Naseem’s voice quivered, “are you sure?”

Bhola nodded. “Anwar is with them,” he added.

Naseem paled. Anwar was Naseem’s older brother. Poisoned by hate that seemed to be in the very air that they breathed, Anwar had started abhorring all those whom he called kafir. Hatred and fury had made him one of the gang leaders of the rioters.

“You need to hurry,” repeated Bhola, his forehead gleaming with sweat in the flickering light of the candle.

Pushpendra clutched Naseem’s dupatta, trailing behind her as she moved like a dervish, making a small bundle of clothes. Opening the big canister, she filled a brass box with the pinnis. Getting down on her knees, she hugged Pushpendra. Giving him the box and the bundle of clothes, she said, “go with Bhola, my dear, he will keep you safe.”

Bewildered, Pushpendra looked at her, “are you not coming with me?”

Naseem shook her head. Her eyes shining with unshed tears, she said, “if Anwar is there with the mob, I will try to reason with him. He will hopefully listen to me.”

The sound of the mob shouting came closer and there was a rattle at the main door as someone tried to push it open.

Looking at Bhola, she said, “Bhola, swear on the Gods you pray to daily that you will take care of Pushpendra. I am sending him in your safekeeping.”

Bhola nodded as the mob started beating on the door.

“Run! Save yourself!” Naseem said, pushing Pushpendra away from her.

Bhola grabbed Pushpendra’s hand, pulling him along. Just then, a stone came flying over the wall, hitting Naseem on her forehead. Pushpendra cried out, wanting to run to her, but Bhola, lifting Pushpendra on his shoulders, ran out of the back door.

Blinded by tears, the last Pushpendra saw of Naseem was her lying on the floor, her face covered by her dupatta.

Pushpendra ran with Bhola through the fields under the moonless night. Dodging the mob, they managed to find an army camp. A few days later, they were sent to a refugee camp in Delhi.

There, Pushpendra overheard Bhola telling a friend that Lalaji had been murdered in Lahore. Anwar had taken over the haveli and found the valuables Naseem had hidden. Of Naseem, there was no news.

Hearing Bhola lament on the perfidy of Anwar and the struggle to bring up an orphan Pushpendra, buried a seed in Pushpendra’s heart. The seed grew into hatred with each hardship of being a refugee in a newly divided India until it consumed Pushpendra. The sweetness of Naseem’s pinnis faded, as did her sacrifice to keep Pushpendra safe. Burying Naseem’s memories deep within, he refused to mingle, talk, or even touch people of the religion he thought had destroyed his happy life. The rituals and prayers of his religion became his crutch to navigate life.

A slight wetness on his hands brought Pushpendra back to the present. It was his tears, now falling unchecked. He looked at the box of pinnis, and picked another one. It was time to let the sweetness back into his life.

The next afternoon, seeing Shoaib walk back home, Pushpendra didn’t wait. He called out, “Hello Shoaib!”

. ** END **

Glossary

Pinni: A staple of Punjabi households in winter, it is a sweet made of flour, ghee, and roasted nuts. Supposed to be healthy and helps in warding off cold.

Doshala: A type of woollen shawl

Adaab: Urdu greeting for hello

Goras: Slang for foreigners, in this case, the Britishers

Toran: a decoration hung above the door in Hindu households

Badi Ammi: usually used to refer to grandmother.

Sevaiyan: A type of sweet made for Eid

Jannat: Heaven

Haveli: old-fashioned mansion

Khichadi: Rice and lentils cooked together.

Voti: Daughter-in-law/Bride

Dua: A Muslim prayer for safe-keeping

Kafir: Non-believers

Harshita Nanda is an author, blogger and book reviewer based in Dubai, UAE. An engineer by qualification she changed tracks to become a full-time writer.

One of the short-listed candiates of Rama Mehta Writing Grant, 2023, her short stories have found a home in many anthologies such as The Blogchatter Book Of Thrillers, The Blogchatter Book of Love, and Lightning Strikes. Her words have appeared on websites like Kitaab, Porch Lit Mag, Roi Faineant Literary Press and Samyukta Fiction

© The Ink & Quill Collective 2025. All rights reserved.

FOLLOW US ON

Or drop us an email at -

theinkandquillcollective@gmail.com

inkquillcollective@arijitnandi.com